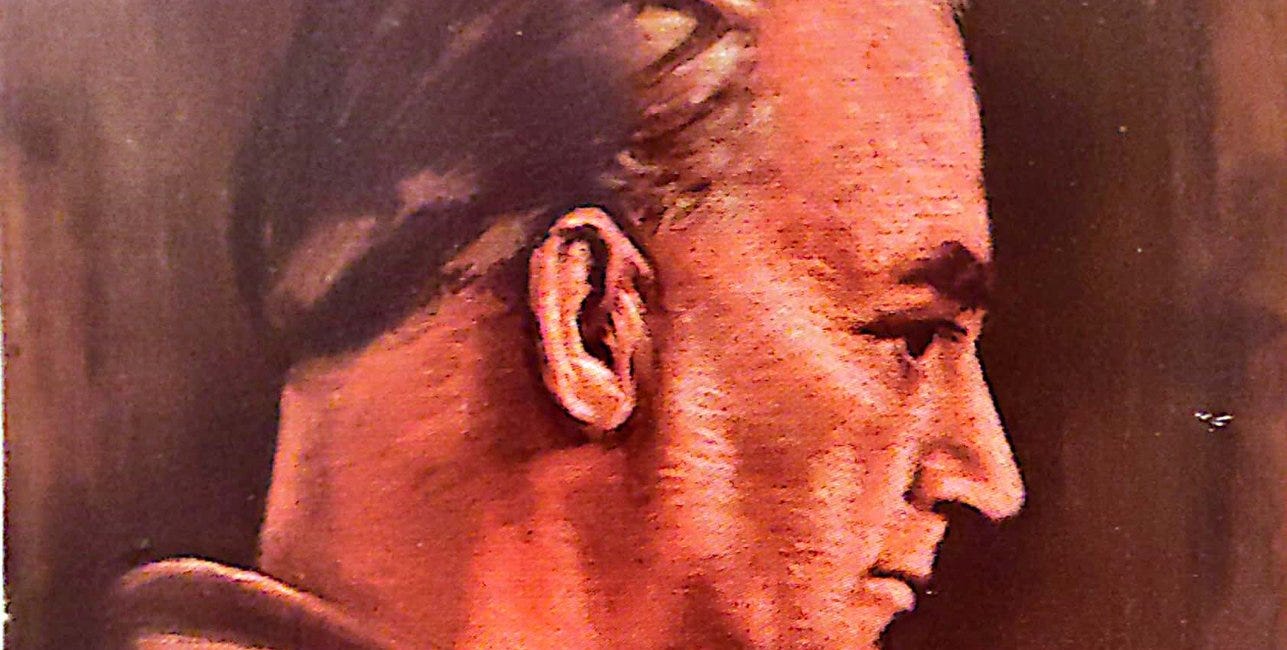

Baylebridge — An Anzac Muster: The Mopoke

Chapter Two of Baylebridge's 'An Anzac Muster — The Mopoke

This is chapter two of An Anzac Muster. Chapter one may be found here:

Baylebridge - An Anzac Muster: The Captain's Tale

Note: Baylebridge was in England when the war broke out, and it was thus difficult to enlist in the Australian Armed Forces. Nevertheless, it is suspected that he was employed by the secret service of the British Government – he was in Egypt, its base of operations, during the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, and he was in contact with troops there. It is po…

WHEN the Captain had finished speaking, the Colonel, with a pleased eye, turned to his brother, and said, quietly:

‘In this telling you’ve had a fair taste of our quality. If you like the matter, care nothing for the plain words; we’ve little art here. Moreover, if the Captain has spoken bravely about the good work of Australians, think not that he’s a stranger to modesty. He did not tell you, as he might have done, that himself stood in the front of the business at Lone Pine, and there took so sore a wound that we despaired long of his life.’

‘A truce to your niceness!’ answered the Squatter, lifting his hand. ‘Not only do I like the matter; I find the style apt and right proper too. This clean telling, to speak for myself, puts a sharp spur into imagination; so that, listening to our friend, I seemed to be on the spot itself.’

These words put heart into the company. Having — most of them — small skill in the tricks of the taleteller, the speakers wondered how the Squatter would receive their narrations. They now believed him such a listener as they should most care for. The Sergeant, it is true, and his friend Ink-Finger, took the speech less kindly; but, whatever their thoughts upon it, it was no time now to show these.

‘And now,’ said the Colonel, ‘since chance has ordained it so, we’ll have something from the Ram. But,’ he continued, turning with a premonitory glance to the new teller, ‘let it not be so bawdy that our guest will blush for it.’

But the Squatter smiled, and said: ‘I am no woman. Why, then, put a proscription upon any tongue here? If my will carries it, each shall have liberty in his speech, each shall tell his tale in his own manner.’

‘Well,’ the Ram put in, as a grin travelled round his red face, ‘it must be like that with me, or not at all. The bread I bring to this table (as I heard someone say once) is plain stuff, with salt and a little yeast in it. Let those who can, serve the fancy dishes. I can’t.’

Then, after taking another pull at his beer, he wiped his mouth, spat, and told this tale.

THE MOPOKE

AT the north of New South Wales, in a small town on the river Tweed, there lived, some time back, a man named Glossop. He was a long loose-limbed fellow, with flat cheeks and a jaw. This man, among other talents, had a good way with girls, and was never without a pick of company in that kind. He led a brisk life. But what man can let his luck be? Going out often with one that worked in a bar there, and getting to like her well enough, he fixed things up with this wench, and all others there put from his mind.

No great time after this the war broke out; and this man Glossop, with others from his part, joined up. Hard, you may think, this was for that wench. Hard, at least, it seemed. She wept like a tap. But there was no help for it: she must needs bid her man good speed; and this, with arms flung about his neck, and broken words, and tears enough, she did. Said she: ‘Sweetheart, return soon. Come what will, you will find me warm as ever.’ Then this man left. He took train up to Brisbane and went into camp near there.

Now, this woman was right fair to look at; and yet, if the best part of beauty is a comely bearing, she was not the fairest woman in that town. No sooner had her bewept man gone off than she dried up her tears, and set herself to the thing that came next. It may be, she was good for action, and cared little to lose time. It may be, she did this to kill sorrow. I can’t say; but she was soon busy again. But, knowing that better dealing is had with men hungry than with those who have had their fill, knowing, too, that, where dogs fight for it, the price upon the bone is put up, she made haste slowly; and this was all to her good. But at last, thinking this best, she settled on one man; and life was again one long holiday.

When some months had gone by, Glossop got leave; he then made off home. Being a poor hand at writing, he sent no word of this. He was nearly there when he fell in with an old mate, and they got talking.

At last, among other things, this soldier said: ‘Bill, if there’s sprightlier doing, there’s worse; stick to one woman — that’s best.’

That other looked straight on. ‘For all that,’ he said, ‘I’ve heard this — where there’s little to wish for, there’s much to fear.’

‘How so?’ asked this soldier. He thought these queer words.

And that other, pulling up, and turning round square to him, said: ‘Mate, in all places you’ll find men with a great itch to help themselves. One like that there is here. He has fixed things up more for his own good than for yours.’ Then, as he turned off up a track there, he said: ‘I’ll be in later.’

‘Tis an old saying that he who knows little will suspect much; that, now, is what Glossop did. It may be, too, he had learn things on his travels; for travel is a great teacher. He sat down on a stump there, and though hard.

Now, as the night drew in, bitter thoughts had this soldier. He brought back to mind those brisk hours spent with that girl — that quiet place roofed in with dark branches (they went always there) — that river, running past like a broad thread of old silver — those mopokes and other night-birds, crying out that the world was empty, and all theirs — ay, and that faithless bitch, yes, her! held hard in his arms. And now what? Now, it might be, she would soon lie stretched out there in the clutch of some other man. Glossop got up. ‘Curse the cow!’ he said. ‘I’ll see.’ At those words he made off, by a roundabout way, to the river; and, coming soon to that well-known spot, the scene of many a tough tousling, up he climbed into the three there, and waited for what might fall out.

If use, as men say, is second nature, and deeds are done mostly after wont, the proof od this could not have turned up more pat than it did here. No sooner was it well dark than along, sure enough, came that wench, and a man holding her. They sat down under that same tree. O God, a right merry sight it would have been then to see that soldier, stuck up there in those branches! When he saw this, a great sweat came out on him.

The couple began now to play. Opening her blouse, the man bit, now here, now there, on the smooth flesh. It so tickled her, she squealed like a sucking pig. It did not stop there either: drawing her skirt up, he bit also into her warm thighs. Then they got catching at one another. Then, giving over awhile because of their heat, they sat quiet.

Said this man then, with a soft chuckle: ‘It looks to me you don’t miss that coot up in Brisbane a great deal.’

She pouted. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘and what then? He’d no great store of pluck. For one thing, he’d never risk a tooth on me, as you do. He’d a spine like a lizard, too.’

No anger, they say, is a weapon already ripe for sharp deeds, and contempt a whetstone to put an edge to it. If that is to, this seemed no very fit time for that soldier to hear these things.

The man below stroked her hip. ‘If he ever comes back,’ he said, ‘I’ll put up a great fight for you.’

Then they stretched themselves out together on the crushed grass.

Hardly now could that solider hold back longer.

Soon they sat up again; and this man said: ‘One would think, to hear these mopokes crying out so, they begrudged us this.’ At that they both laughed.

‘As for them,’ she replied, ‘’tis no matter. But if Dick was a mopoke now, and looked down from one of these trees, need enough, then, there’d be to pray for fair weather.’

‘Alas! she feared little for her waggish words. Men say that luck is blind, and yet not hidden; not so did that seem here.

Then this man had a thought. Squeezing hard on her plump hand, he said: ‘Sweetheart, there are things that ought to be kept dark; this is one. If it leaked out that we made so much of one another, that would do neither of us much good.’

For some time the woman held her peace. ‘That may be,’ she said then, slowly. ‘And yet there is something, too, that would be liked still less.’

‘What,’ said this man, ‘is that?”

And this woman said, softly: ‘I go with child.’

Take though, mates, how much lies in the two hands of Occasion! She can mend and mar mightily with those two hands of well-timed and ill-timed. And of all those things ever timed ill, none, surely, could have been more so than this.

Said this man then: ‘That’s tough news. What shall we do about it?’

‘Well, not lose sleep,’ the wench replied, laughing. ‘Seeing you make yourself out but a poor man, I mean, if you’ll keep quiet, to let Dick father it.’

Now, this was the last straw. Hearing this, that soldier could hold no longer. Hot with rage, down he sprang from the tree. He struck a match, and held it up against their scared faces. ‘Not so!’ he said, with a hard eye. ‘This filth shall be shot into its own yard.’

Then, looking squarely at that woman, ‘God strike you stiff,’ he said, ‘for a crooked slut!... But luck has done me a good turn here.’

‘If you ask, now, how that other man took all this, I will tell you — he felt a great chill at his spine. For him, now, all the savour had gone clean out of this thing.

Edging away somewhat, he said, quickly: ‘Out of no ill will to you, look, did I do this, no, but for pleasure’s sake.’

That soldier turned on him hotly. He could wait no longer. Catching him quickly by the scruff, he ran him down smartly to the bank of that river, and, helping the business with his boot, out he flung him into the chill water. Down he sank, head first into the mud there; he stirred up many a thick mouthful of this. If you ask how he felt then, I doubt little but he was not praising God overmuch.

Said that soldier grimly, seeing him there: ‘If you think a man, hearing such talk, will from that get comfort, why, then, have this now from me. I, too, did this out of no ill will, no, but for pleasure’s sake only. For all that,’ he went on, with a firm mouth, ‘there’s one thing we differ in: though you would hurt me in the dark, little bones shall I make about letting in as much light as I can on to this hurt done you.’ He then turned back to that woman. ‘You asked me,’ he said, ‘to come back soon; too soon, it looks, have I done that. But the truth is, as you then gave your pledged word I should, I find you yet warm as ever, or, rather, more so.’

For shame’s sake, that woman said nothing. Moreover, she had little will to hurt herself then with words.

Said that soldier then: ‘I will now let my former liking speak up for you. Grounds enough, no doubt, you had for this trick. Love and fair reason, they say, are not found in one skin; and a man of push, I know, is more in face with your sluttish kind than one too nice. It may be, a change in weapons, and a new style of conducting the warfare, helped him.’ At that, near choked again with his heat, he stopped short.

‘And now,’ he said, once more cooling a little, ‘since I’ve got level with this dirt, I’ll not keep my sores open thinking about it. They’ll do well enough now.’ And, saying that, he turned away, and made off to the town.

Once there, he did not let this joke stale. Not so: decking it out in all its detail, he did what he could to keep it moving. So well, too, was this done that that other man found he had taken up more than he could well hold; ay, he found he had stirred up more than he could lay again.

This jest became a great favourite in that town. Bringing to mind those quaint words about the mopoke, and considering how nicely they had hit the truth off, men there, from this on, nicknamed this soldier after that most elusive bird. They would say, laughing: ‘A neat job! That mopoke was a shrewd bird. What!’

***

A LAUGH went round; nor did the more sober members of the company stick to join in it too. These last, it is true, rather smiled than laughed; but the Ram thought this a sufficient comment. His vanity, not to mention his mother-wit, prompted him to believe that, among men of any depth, we must look not for that facile expression of emotion that comes so readily with other kinds. He was well pleased with himself. His only rival on this ground, as he knew, was Ink-Finger; and Ink-Finger was already busy, thinking out some yarn that would get as good a reception as the one just told.

When the laugh had died off, and various judgements on the behaviour of the old gallant and the new had been expressed and argued upon, the Colonel, thinking it time now to alter the tune, said:

‘I doubt not but the Ram, and I fear others, will have a stock of these lecherous tales. All the more readily, then, shall we now hear what the Pilot has to tell us; for, as I see by the board, he’s the next teller.’

The Pilot, for some minutes, had been lost in thought. Gazing beyond the circle of quiet light cast by the lamps, he seemed to be wandering in some region removed, in some region, perhaps, where the affairs of the warm humanity about him had no place, or little — who could tell? However, hearing his name, he came to earth again, and said, slowly:

‘To some among us this tale will be no new thing. It needs better words, too, and more skill to them, than I have. But it ought to be told often. In the best way I can, then, I’ll tell it.’

Note: The mopoke (the Australian boobook, nunox boobok) was also called the cuckoo owl, hence the title.